Anglès legends

The town of Anglès is enriched by a fertile oral tradition that has given rise to a number of legends. Supernatural beings, witches and the Devil himself. Enter a fantastic world, meet the legends of Anglès…

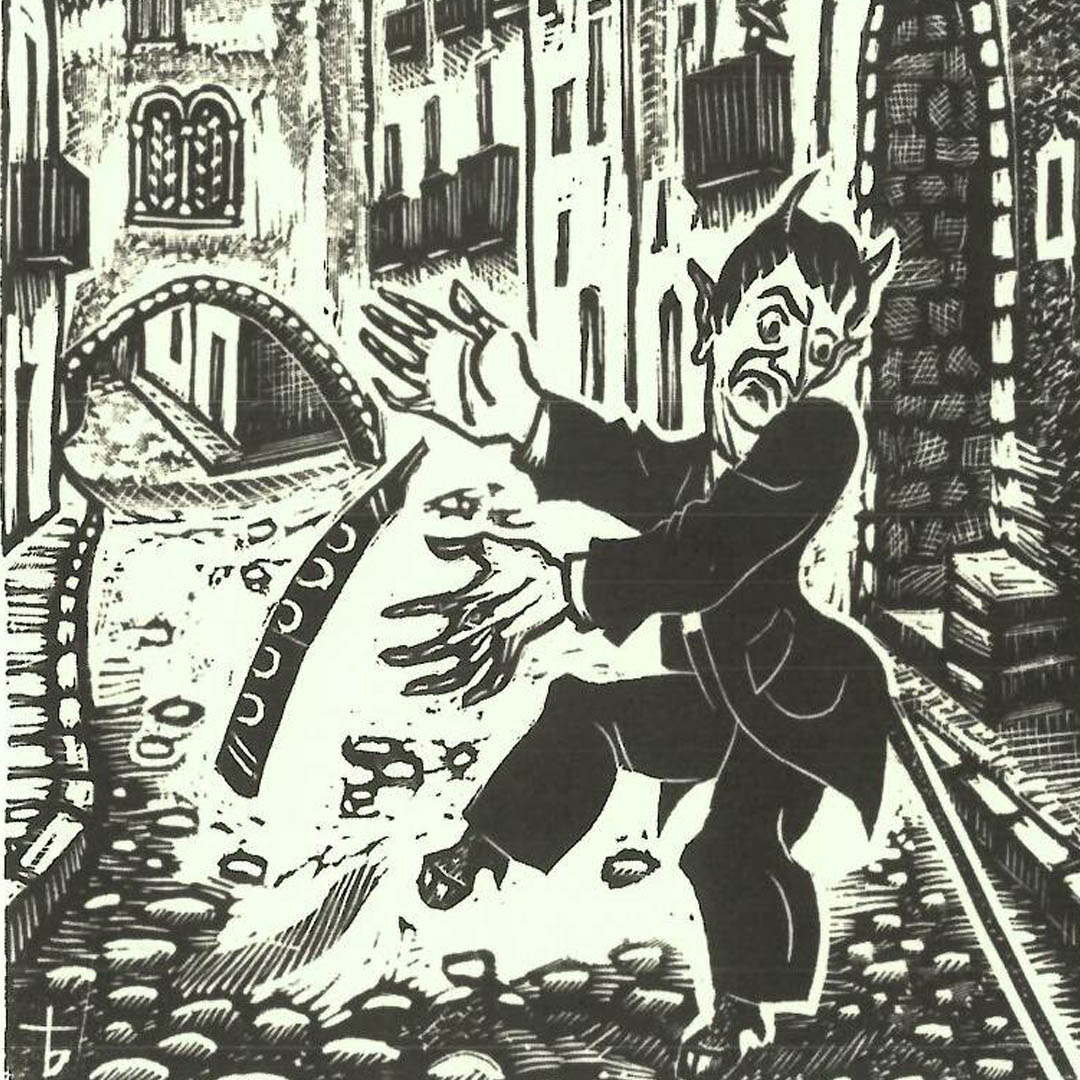

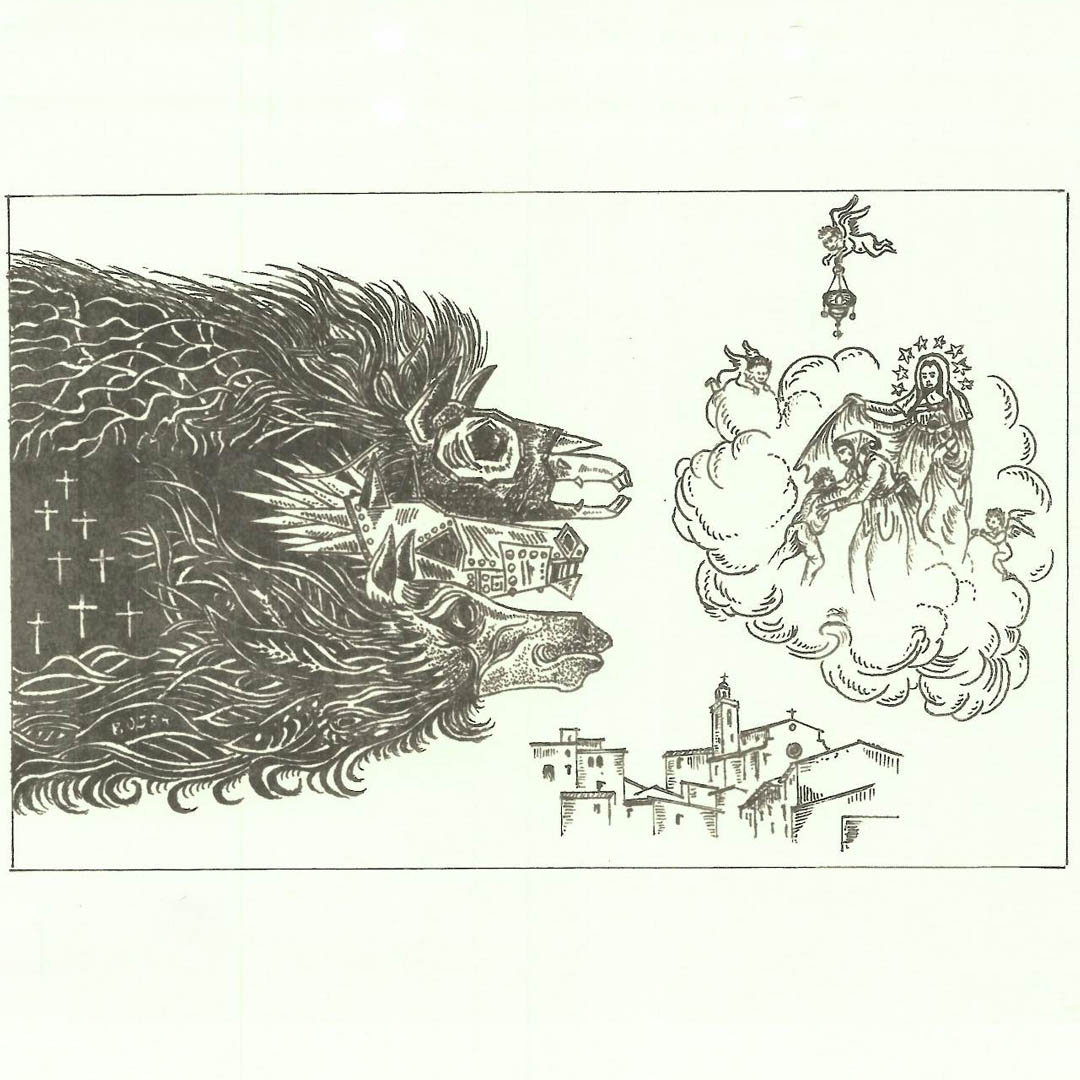

‘The devil is in Anglès’

The legend goes that, on one Saint Anthony’s Day long ago, there were no musicians for the town festival. Eventually, someone said, ‘I’ll find a band, even if it’s a band of demons’. Not long after he had set off on his mission, he got chatting to a stranger he met and they quickly came to an agreement: the stranger would get him his much sought-after band. The band was too late for mass, as it was the day of the festival, but they got there on time for the sardana dancing However, when they were asked to play the ‘Contrapàs de la Passió’ – a traditional Catalan religious dance – the musicians flatly refused, and most of them ran away, except for one,whose ‘tail got stuck, and he’s probably still there today’. Hence the local saying: ‘The devil is in Anglès’.

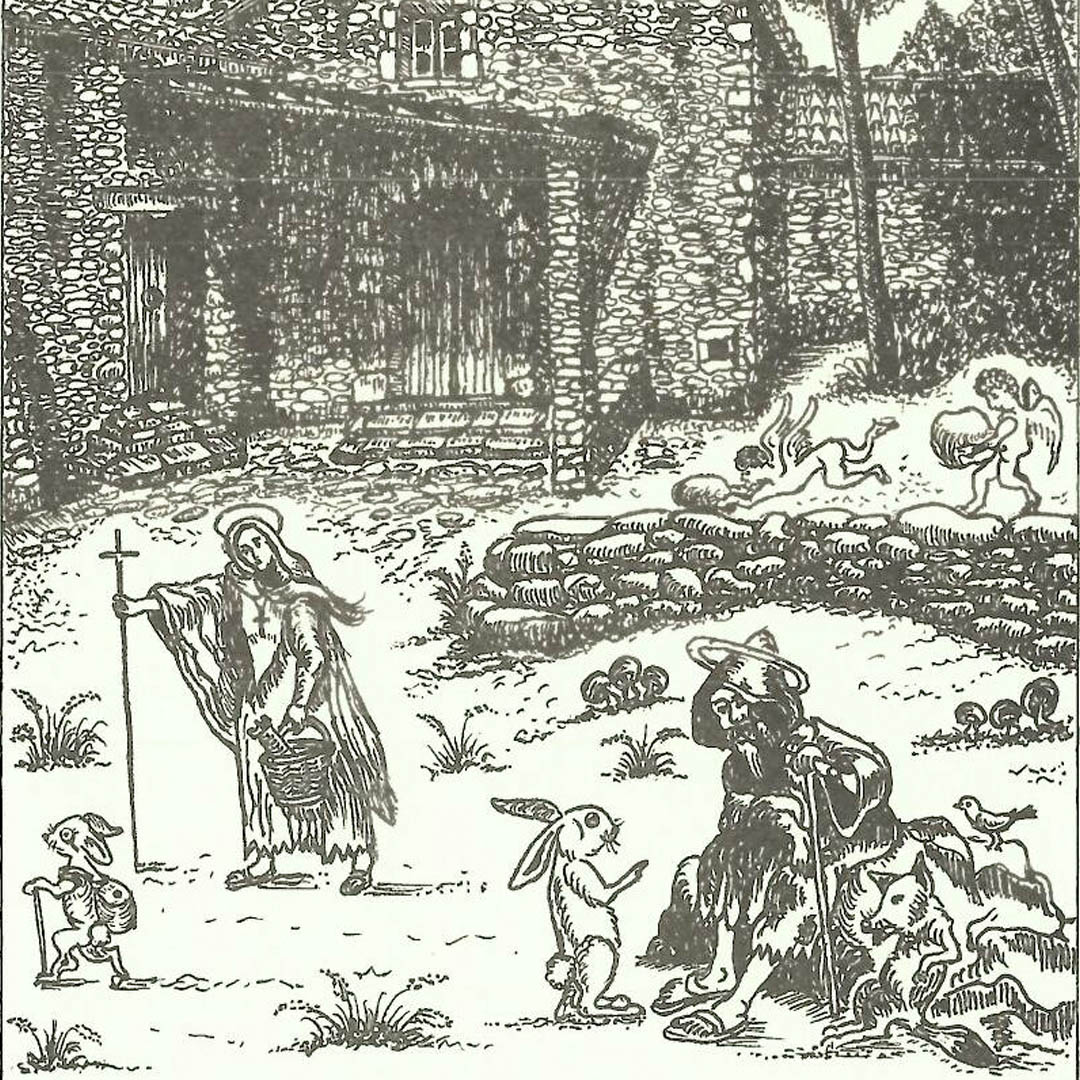

The Witches of Anglès Castle

The work of Catalan folklorist Joan Amades tells us that, once upon a time, Anglès Castle acted as a meeting point for all the witches in the area, who travelled there on their broomsticks.

Now, it’s important to remember that these witches came in all shapes and sizes and from all walks of life. At midnight, they left the house without making a sound, when everyone was sleeping. If they were married, they left a log in the marital bed, so that their husband wouldn’t notice their absence, should he awake. If they had children, they spat three times on the floor, and the three balls of spit would answer if the little ones called out to them. Before applying the ointment they needed to be able to fly, they put two cauldrons over the fire: one filled with broth, so that they could recover with a nice stew when they got back, and another for boiling the herbs and poisoned creatures to help them with their misdeeds.

After all this, they gathered up in the castle, hardly any of which survives today. There, they danced the ball rodó, a traditional Catalan circle dance. If they wanted to start a hail storm, all the witches urinated in a hole, and when it was full, they hit it with an ash wand with nine knots. All of a sudden, a hail cloud would emerge from the hole. This enraged the farmers, so they waited for the witches and beat them with the handles of their tools, every blow breaking a bone.

The Souls’ Bell

Near the old castle was one of the most majestic manor houses in the valley, which lovingly and dutifully looked after a hundred-year-old bell. Tradition says that, every evening, the heir to the manor went onto the town square, holding the bell and reciting prayers to help the souls of the dead and to ask Saint Roch and Saint Sebastian to protect them from hunger, war and the plague. The locals followed his prayers from their front doors. He then began to ring the bell up and down: ding, dong, ding, dong. At various points on his route around the old town, he stopped to pray again.

It was prophesied that on the day the Souls’ Bell was not rung, that old dynasty would die out, and that is exactly what happened. In the last Carlist War, as soon as the heir left the house – as he did every evening – he was stopped and beaten by a group of soldiers who couldn’t care less about the tradition. That was the last time the Souls’ Bell was seen or heard.

La Font del Canyo

Passeig del Canyo is one of the most beautiful, well-loved spots in our town, thanks to the work done on it by municipal architect Joaquim M. Masramon in the 1940s. Though we know it as a green space today, it used to be very different. Its current peace and tranquillity contrasts starkly with the misfortunes that occurred there in olden days.

According to tradition, in those parts there was one of the most important farmhouses in the region. Its lands were fertile thanks to an abundance of water from the fountain next to the big house. The home’s inhabitants were known for their arrogance and their miserliness; it was no coincidence that they were among the richest farmers in the county, and they had plenty of children to whom they could pass on their wealth. At the market in Amer, they were known for wanting to have their cake and eat it too.

But then, one fine day, a devil dressed as a vagabond knocked on their door, asking for alms. The lady of the house sent him packing. Next, the vagabond asked if he could drink from the family’s fountain, but the lady of the house refused, claiming that they needed that water (despite the copious stream gushing forth). So, the man put a curse on the house, and the fountain immediately ran dry.

The lands became barren and the opulent farmhouse deteriorated gradually, until disappearing entirely. It was then that the fountain began to flow once more. In fact, two more outlets were created, such was the intensity with which the water streamed out of the fountain. Abundant, verdant vegetation began to flourish once again on the surrounding lands. Nonetheless, it seems that part of the curse survives today, as none of the three streams of water is clean enough to drink.

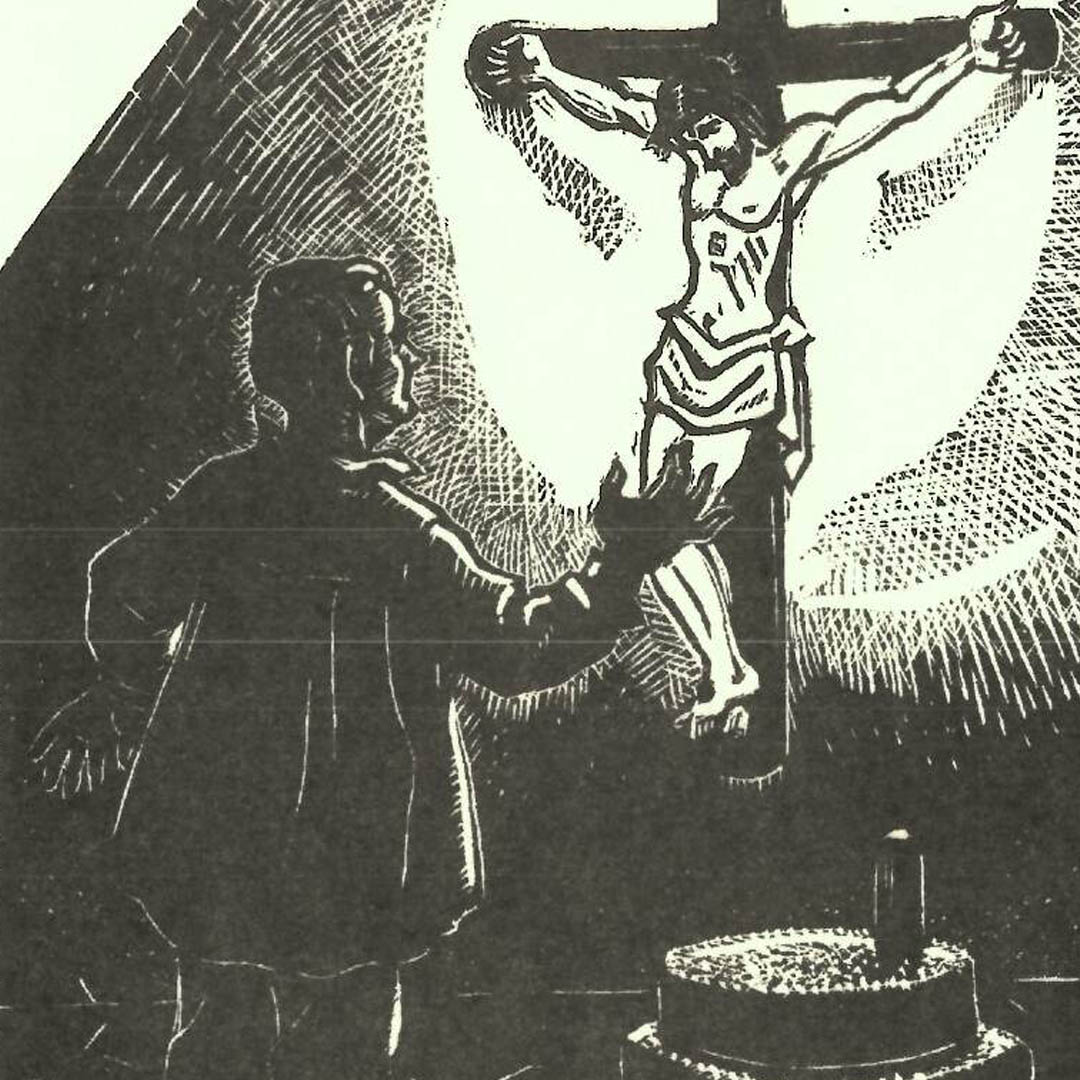

Cuc Mill

The story of Cuc Mill is inextricably linked with the old house built by the nobleman Cuc, who held the title of Familiar of the Holy Office and had his own chapel and tomb in Sant Miquel Parish Church. Legend has it that one day, the miller at Cuc Mill went to confess, perhaps out of remorse. While listing his various faults, he quietly admitted that, when he gave back the wheat that had been brought for milling, there was always a little bit left at the bottom of the sack after he poured it into the hopper, and of course, ounce by ounce, he saved it up for himself.

The priest felt compelled to scold him, and as the miller retorted that he couldn’t help himself, that his hands did their own thing and he could never pour in the whole sack, the clergyman gave him a crucifix to look after the mill. That way, when the miller saw it, he would not feel the urge to steal other people’s wheat. Everything went swimmingly for a few days, but soon, the miller found himself at the brink of ruin. One fine day, before starting work, he squared up to the crucifix and blurted,

‘Look, boy, you and I need to have a serious chat, because ever since I started following your advice, I’ve been down on my luck. If we go on like this, one of us will have to be on our way, because we won’t even be able to fill our bellies. And as I’ve been here longer, it’s you who needs to scarper’.

That’s exactly what happened: the miller grabbed the crucifix and threw it outside. From that point on, he went back to his old tricks, and the wheat went back to sticking to the bottom of the sack like before. Of course, you can change the miller, but you can’t change the thief.

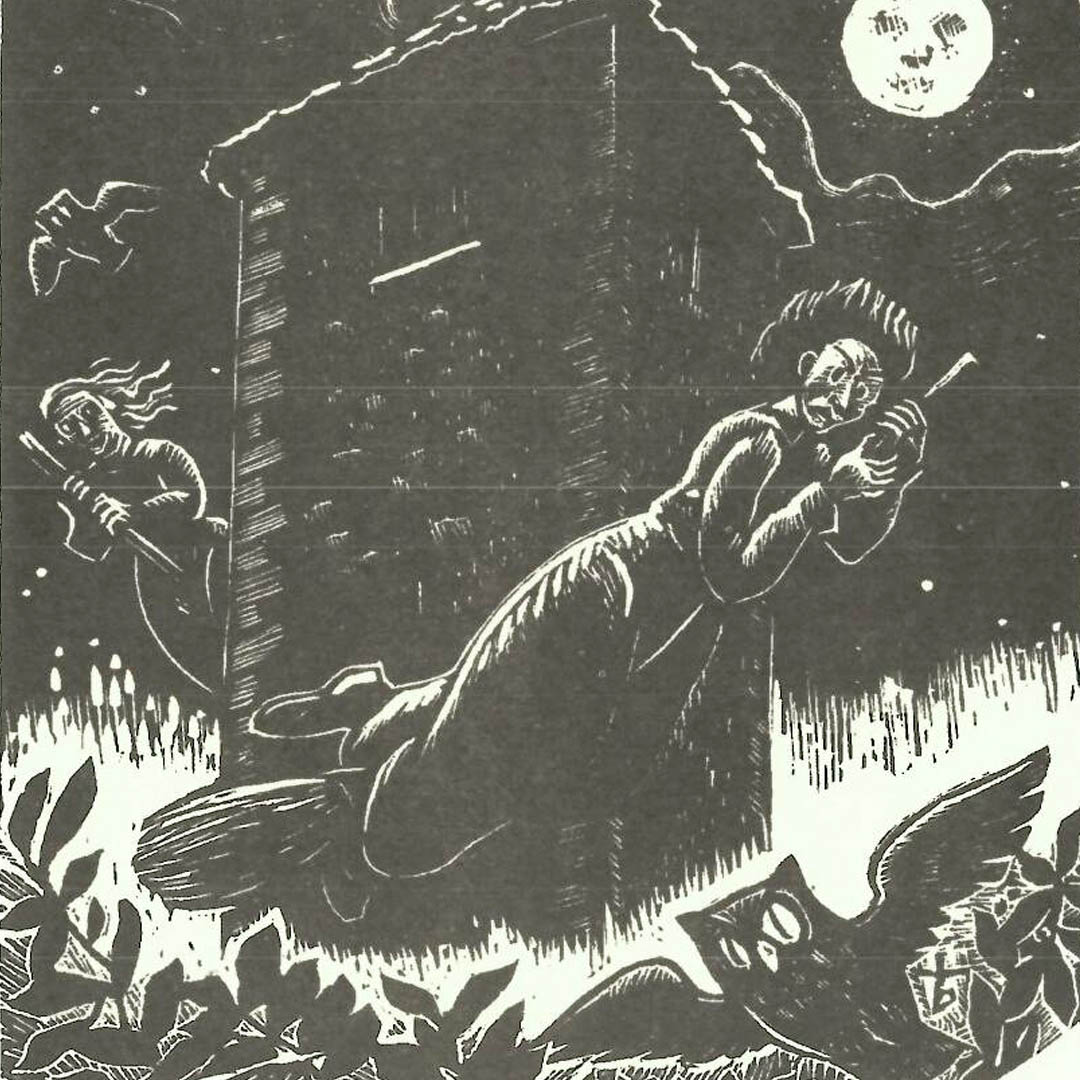

The Bride of Can Biel

Can Biel is one of the oldest, most eye-catching fortified farmhouses in our town. But despite its apparent opulence, the house has always been shrouded in melancholy. They say that, once upon a time, the family’s son was to celebrate his marriage to a wealthy heiress from the area. Everyone was there at the wedding banquet: the priest, the provosts, hebdomadarians… The great and the good. All of the region’s landowners were represented, and even the odd canon.

After the big reception, it was time for dancing and entertainment. It was decided that they would play hide-and-seek. Everyone was keen to find the bride, but she put a lot of effort into hiding so that no one would find her. In silence, she climbed up the stairs to the house’s tower and hid inside an old dowry chest she found there. But, horror of horrors, when she managed to squeeze herself inside, the box slammed shut and she couldn’t get out again.

The tower had fallen into disuse, because banditry was no longer an issue, so no one went up there anymore. Meanwhile, downstairs, everyone was busy looking high and low for the bride, in every nook and cranny, but they couldn’t find her. Eventually, they gave up and shouted out to the bride, telling her to come out from her hiding place. After a while, as they saw that there were no signs of life from the bride, the wedding guests’ joyful smiles turned into worried expressions. The guests went home at the end of the evening, and the poor groom was left with nothing but grief. In neighbouring villages, there were rumours that the poor bride had fallen into the Ter in the black of night and been swept away by the current. Others said that the disappearance was down to Ramon Felip’s men, who had been up to no good in the area years before.

Long after, by chance, a girl from the farmhouse went up to the tower and opened the dowry chest. She was met with a pile of bones wrapped in a beautiful wedding dress, accompanied by wedding jewellery.

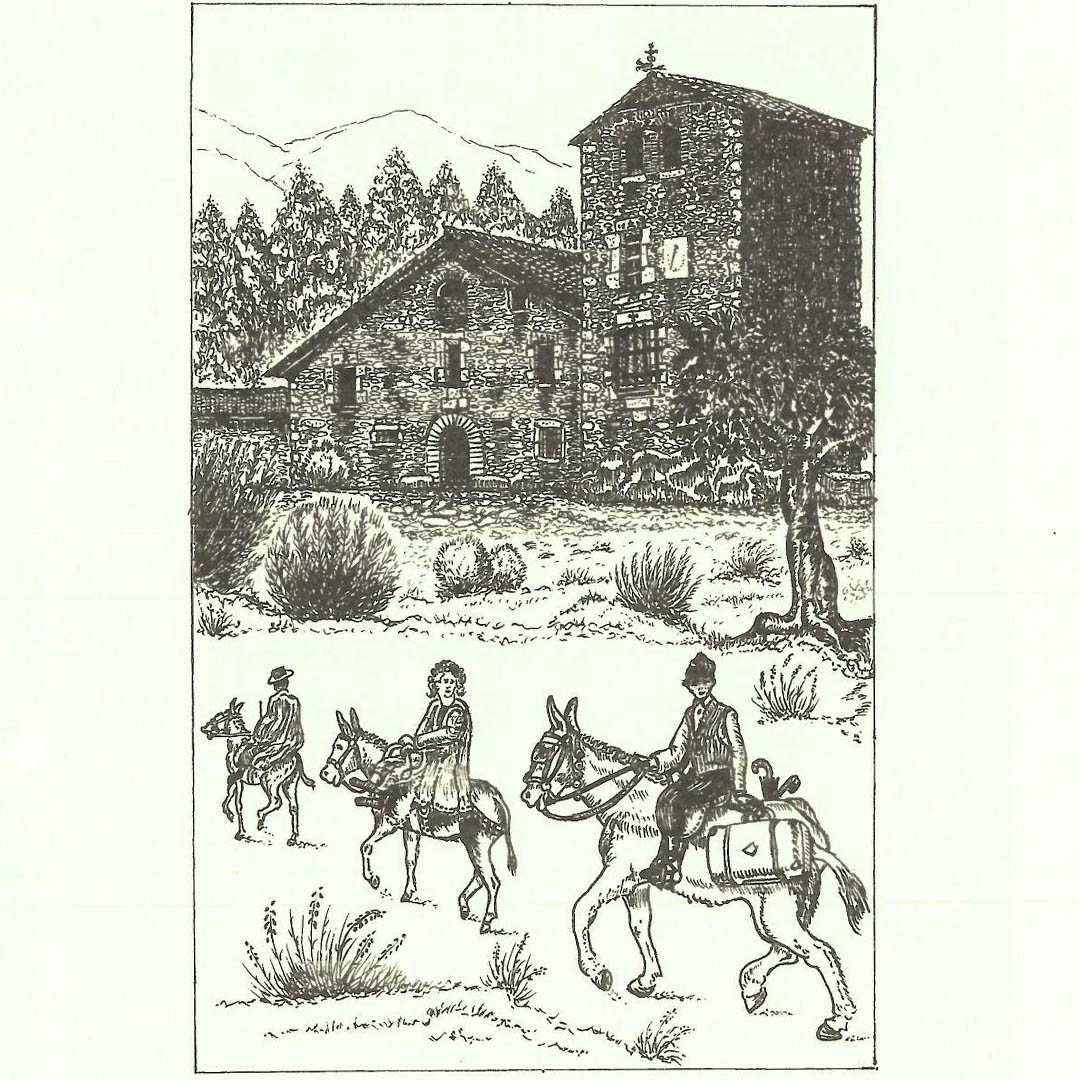

Sant Pere Sestronques, Sant Amanç and Santa Bàrbara

The story goes that, one day, three saints coincided on their journeys: Saint Peter, Saint Amantius and Santa Barbara. As they approached Sant Martí Sapresa, Saint Peter got tired and decided to rest. As he came from the coast and wasn’t used to walking in the mountains, he looked at the steep path ahead and told his companions to carry on while he got his breath back. In the end, he decided to stay in that same spot, and that is how Sant Pere Sestronques Church was founded.

Determined to carry on with their journey, Saint Amantius and Santa Barbara made their way up the mountain, but not long after, the former started to complain of fatigue and a sore back. So, he decided to stop and rest on a small hill, on which he built a cabin. The construction would go on to act as a spiritual retreat for the households in the area, until the locals contributed the money and labour needed to build the new Sant Amanç Parish Church.

Saint Barbara, unfazed by her companions’ withdrawal from the journey, continued along her arduous route. So determined was she that she didn’t stop until she reached the summit. Admiring the magnificent views from the top, she decided to build a small, wooden refuge there. Later, through reinforcement with stone and the creation of a chapel, it became the Santa Bàrbara Hermitage we know today. Saint Barbara lived there for many years, but now, we only think of her when it rains or there is thunder. Proof of this is in the Catalan expressions: ‘Quan Santa Bàrbara porta capell, pluja pel clatell’ [When Saint Barbara’s got her hat on, you’ll feel raindrops on your neck]; and ‘Sant Marc, Santa Creu, Santa Bàrbara no ens deixeu’ [Saint Mark, Holy Cross, Saint Barbara, don’t leave us], an invocation used during thunderstorms.

Miquel of Sant Amanç

The most culinary legend surrounding the village of Sant Amanç goes that, in the late fourteenth century, Elionor de Cabrera, the lady of Anglès Castle, invited her courtiers to a banquet, featuring all the best meats from the area and the nouveau wine from the last harvest from the vineyards of Puig Vell. Among them was a lean meat carefully prepared by one of the cooks: a man from Pisa who had just come back from some of King Peter’s campaigns. What Elionor didn’t know was that the cook was nothing more than a demon in disguise who, having been forced to leave the service of the king before he could poison him (as he had done with James of Urgell), had come up with a plan to exact revenge on the lady of the castle. Anyway, the cook prepared some meatballs using lean meat and mushrooms – which he had mixed with a considerable amount of highly toxic Satan’s boletes – and wrapped them in their coating. But the servant, a boy from Sant Amanç, was clever and saw what the troublemaker was doing, so he served the meatballs without the poison, which he replaced with a delicious parsley, garlic, egg and saffron milk cap garnish. The guests seemed to be satisfied with the food. Elionor headed to the kitchen to congratulate the cook, but before she could say a word, he responded to what he thought would be a scolding and blamed the poisoning on the kitchen hand, thus revealing his scheme. Before the demon could realise that he had put his foot – and tail – in it, Elionor had him imprisoned in the castle’s darkest underground cell, which he would never leave, and named the young kitchen hand, Miquel of Sant Amanç, as the new cook. That is why this dish is known as Elionor’s or Sant Amanç meatballs.

Even today, the residents of Carrer del Castell say that, on Saint John’s Eve, they can still hear the demon wailing about his unfortunate end.

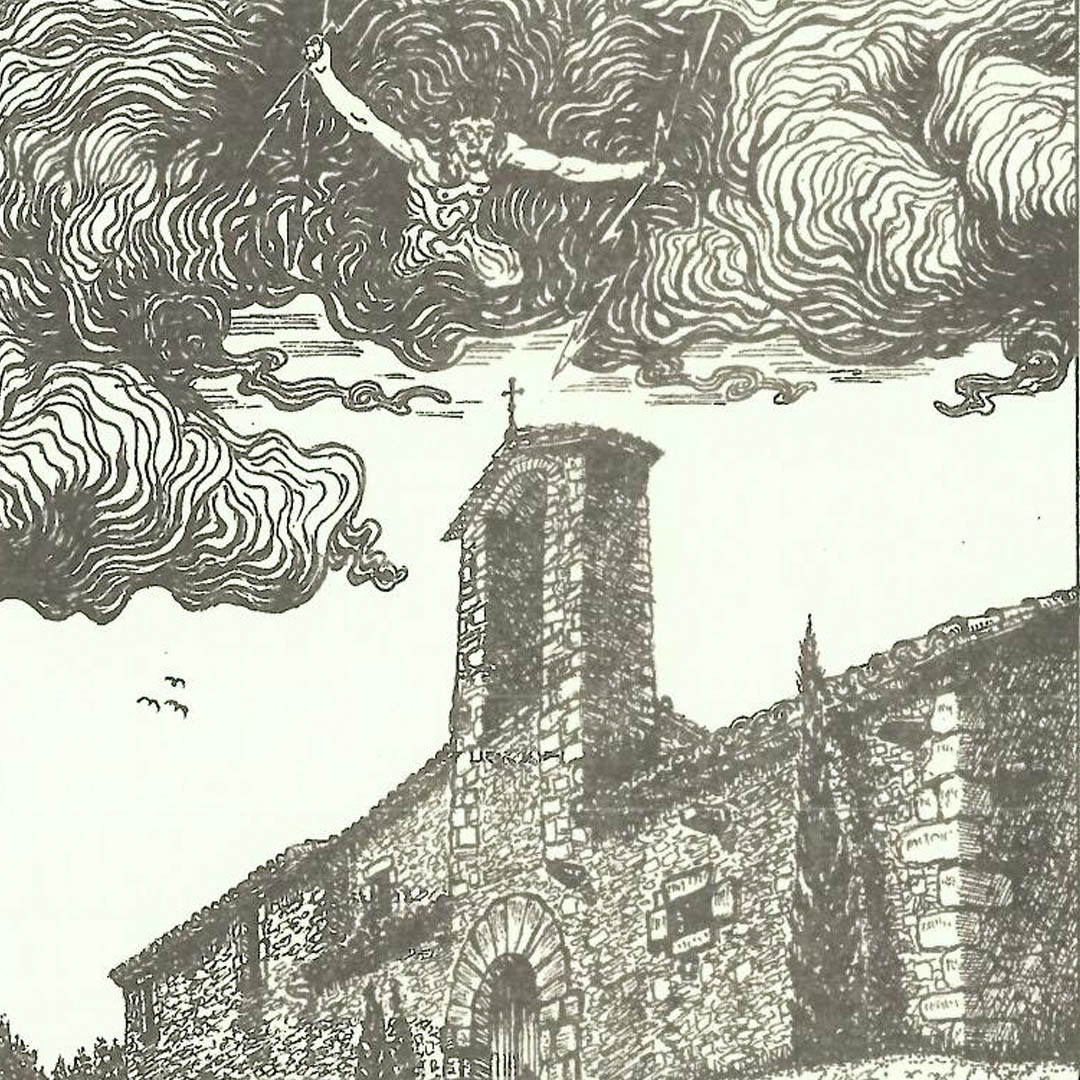

The Witches’ Tower

Over the course of history, witches have come in all shapes and sizes. Even round! And they have always had supernatural or magical powers, thanks to their pact with the devil. You will find more of them in some places than in others, but every village, town and city has had them. Llers is well known for being a witches’ village, but who would have known that many of them would choose our little valley to settle down in and cast their spells.

In fact, the old bell tower in the parish of La Cellera is widely known as the ‘Witches’ Tower’. It would seem that witches from all over used to come together there, which led the townspeople of La Cellera and Anglès to ask the Dominican friar and famous inquisitor Eimeric of Girona to intervene.

Indeed, it is well known that, on the coldest days of winter, if you go behind Santa Maria de Sales Church, in front of the street where the old bell tower stands, and listen out carefully, you might hear the wails of witches yearning for their old haunt.

Our ancestors must have been sick of witches, between the witches of Anglès Castle, who rode on billy goats, and the ones who met at the old bell tower in La Cellera, who favoured rams.

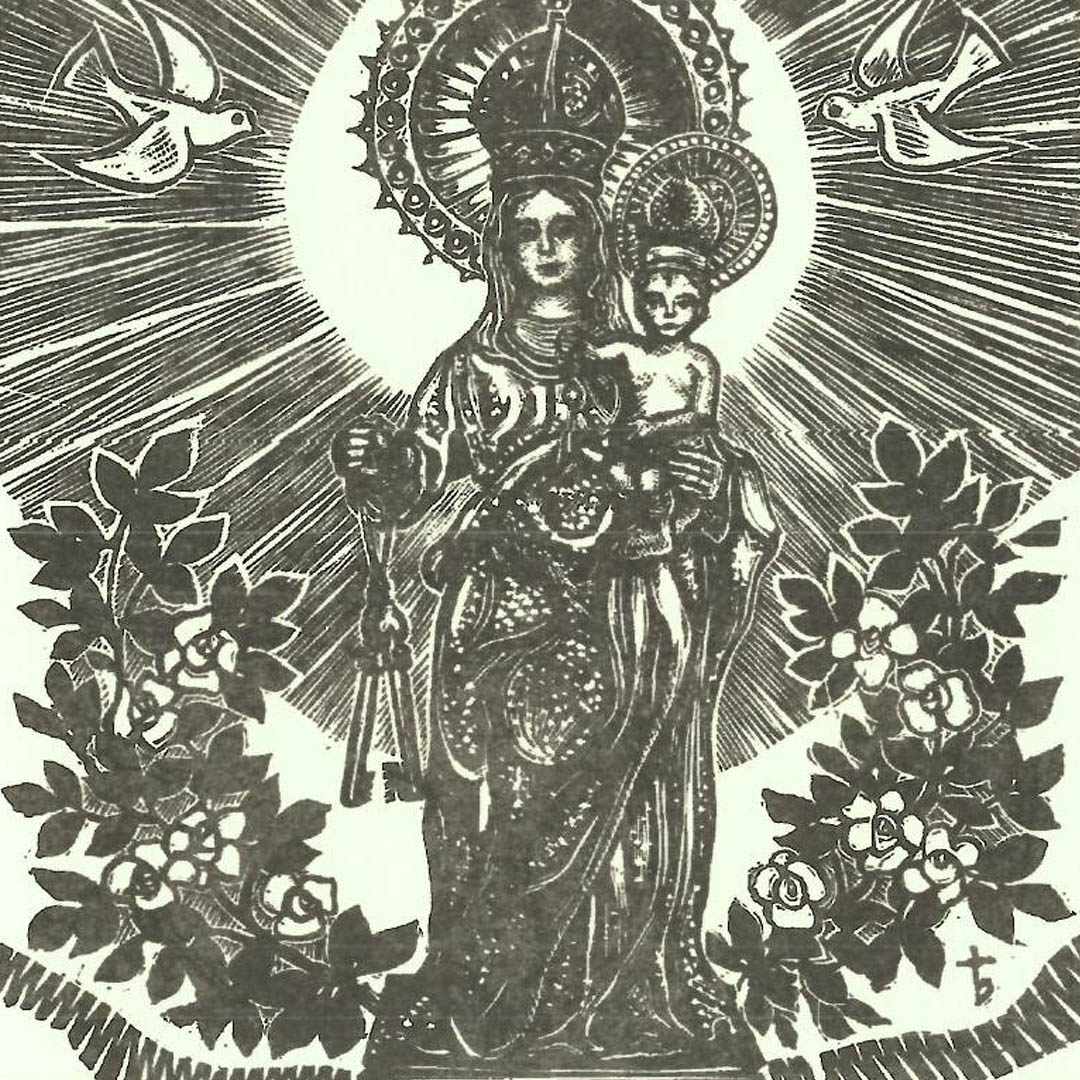

The Virgin of El Remei’s Protection: War and Plague

The patron saint of Anglès is the Virgin of El Remei, who protects the town’s population against misfortunes. She is often invoked by the faithful to remedy all kinds of illnesses and pains.

A long time ago, the people of Anglès paid tribute to the Virgin of El Remei when she saved the town from pillage by French troops. The story goes that, around the second half of the seventeenth century, during one of many French invasions, all the neighbouring village were pillaged and looted for food by soldiers. When it was Anglès’s turn, the townspeople, protected by the old castle’s defences, were able to resist the attack. The French troops were annoyed, and as they headed to Olot, they decided to seek revenge. So that they could take the townspeople by surprise and the castle guards wouldn’t warn them of their arrival in the town, once they reached the Trullàs plain, they followed the River Ter upwards until getting to Sant Julià. All of a sudden, a thick fog enveloped the whole town and made it entirely invisible. The invaders didn’t realise they had gone past it until they had reached El Pasteral. Then, the officer leading the troops asked who the town’s patron saint was. When he found out it was the Virgin of El Remei, he exclaimed, ‘Well, may they preserve her and worship her, because she has saved them from very grave danger today!’.

As thanks, the people offered the Virgin some keys made of the finest silver, as a symbol of her protection. Though the old image was destroyed (20 July 1936), these keys still hang today from the right arm of the new image.

And she didn’t only save us from war; she protected us against the plague, too. Father Lluís Constans wrote that, in 1653, the plague was devastating many of Catalonia’s villages. Seeing this disaster and fearing the plague might reach their town, the people of Anglès prayed solemnly to the Virgin of El Remei, who saved them from this terrible fate. Our neighbours in La Cellera weren’t so lucky; the plague was unleashed on them in all its cruelty. To show their gratitude, the townspeople commissioned Joan Francesc, a silversmith from Girona, to make a silver lamp, which still burns today. If it ever stops, someone should tell that godless French soldier who tried to light his cigar with it, but every time he tried, the flame went out. Of course, as soon as he moved away, the flame started burning again.

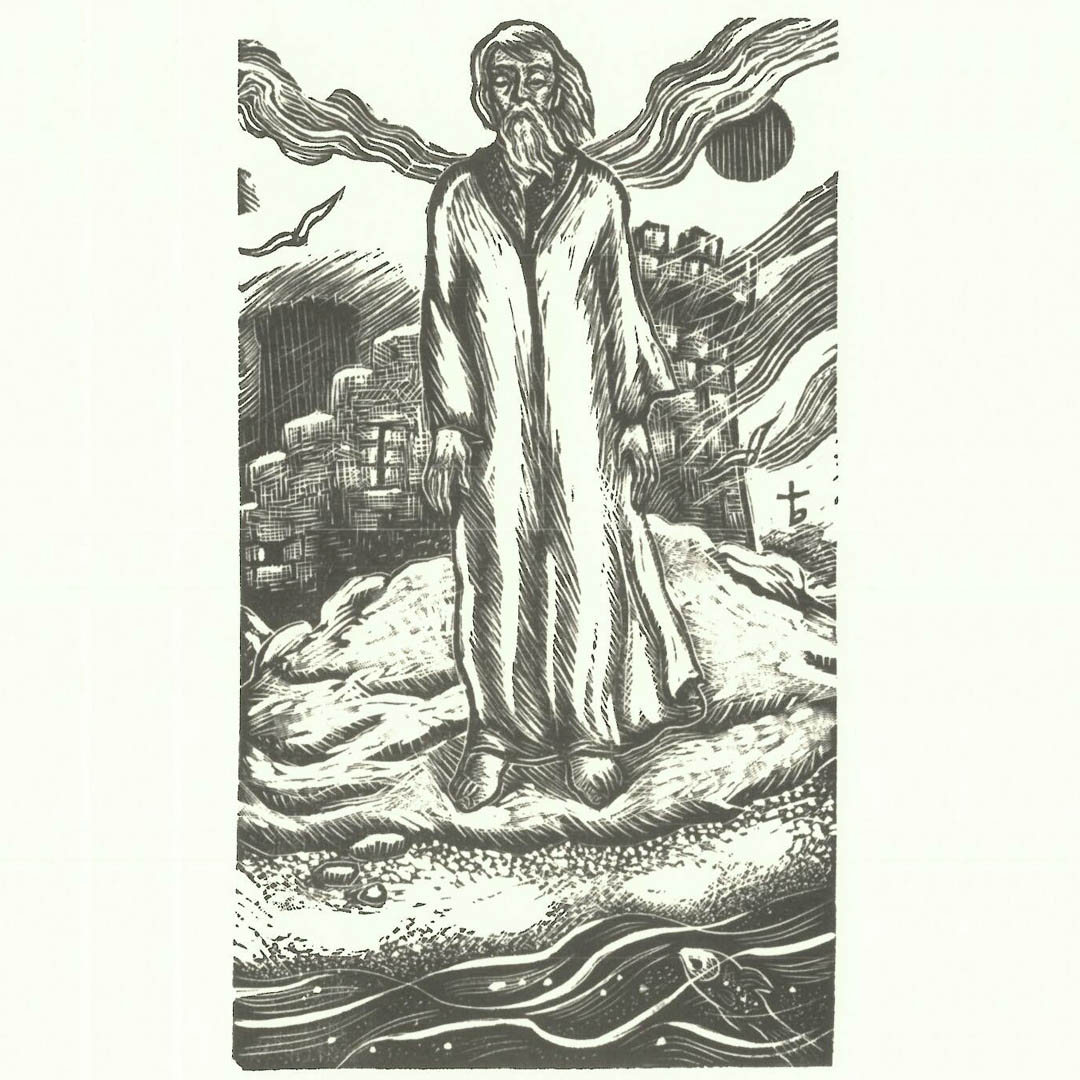

Anglès Castle Rock

Long ago, the River Ter was flowing by peacefully at the foot of the rock on which Anglès Castle was built. According to tradition, in that bygone era, a handsome, mysterious stranger appeared in the Anglès Valley. Nobody knew where he was from, what he was called, why he was there. Early in the morning, when the rising sun’s light started to wake up the plain and the new day peeked through the neighbouring mountains, the mysterious foreigner sat down on the castle rock, from which he would not budge until the shadows of twilight laid their black cape over the half-asleep valley. Everyone wondered what he did there for so many hours, plonked down on that rock. One old know-it-all said that the foreigner spent his days watching the fish in the River Ter. And that’s how the surname Miralpeix came about – from the Catalan ‘mirar el peix’, meaning ‘to watch the fish’ – and gave a name to one of the most important dynasties in the history of our town.

The creation of this website has been carried out in the framework of the execution of Operation 7 of the PECT Girona, Active Heritage, 50% co-financed by the FEDER Operative Program of Catalonia 2014-2020, charged to the budget from the Generalitat de Catalunya, and 25% from the Diputació de Girona.